The Vienna Secession: A History

By: Roberto Rosenman

Take a stroll along the Ringstrasse today; the former location of Vienna’s city walls, and one finds a pastiche of 18th century neo-classical architecture built mostly as a showcase for the grandeur of the Habsburg Empire. Labelled as a ‘Potemkin City’ in the Secession magazine ‘Ver Sacrum’, the Ringstrasse came to symbolize the stifling attitude towards the arts that predominated in a society content with recycling classical styles rather than embracing the new modernist styles that were budding in the rest of Europe. There was a Neo-Greek parliament, a gothic City Hall, Neo-Baroque apartment buildings and most importantly only two exhibition bodies favouring classical-style art. It was in this environment that the first seeds of the Secession movement began to germinate, led by a group of artists who searched for a synthesis of the arts and a place where their new works could be exhibited. Eventually, a new building unlike anything ever seen would appear just off the Ringstrasse signalling a rejection of historicism. It would be the new exhibition hall for the Vienna Secession built by Joseph Olbrich and above it’s door a motto for the age: “To every age its art, to every art its freedom”.

Two principal institutions dominated the Visual Arts in the years prior to the secession: The Akademie de bildende Kunste (the Academy of Fine Arts) and the Kunstlerhaus Genessenschaft – a private exhibiting society founded in 1861. One of the earliest Ringstrasse buildings, the Kunstlerhaus was designed in the style of an Italian Renaissance villa and it became Vienna’s main exhibition hall often under the presidency of conservative bureaucrats. Any established artist at the time belonged to the Kunstlerhaus and each year their work was either selected or rejected for public exhibitions. In this juried selection, it was not uncommon that impressionist and modernist works were rejected in favour of the prevalent naturalism of academic painting. Modern-thinking artists in Kunstlerhaus began to meet regularly at either the Café Zum Blauen Freihaus or the Café Sperl in order to exchange ideas and discuss the work of new artists like Meissonnier and Puvis de Chavannes in France. Eventually, these meetings would result in the forming of two informal art societies. The ‘Blaues Freihaus’ became the home of the ‘Hagengesalleschaft’ or Hagendbund and its members included many future Secessionists: Adolf Bohm, Josef Engelhart, Alfred Roller, Friedrich Konig and Ernst Stohr. Café Sperl became the home of the Siebener Club (Club of Seven) formed in 1894-95 which included Koloman Moser, Max Kurzweil, Leo Kainradl, and the young architects Josef Hoffmann and Josef Olbrich. While the Hagenbund tended more towards naturalism and the Siebener Club towards stylization, both groups shared a commitment to new art and frustration at what they saw as a stagnation of the arts by the Academy and the Kunstlerhaus. Even Gustav Klimt who had by then risen to fame as a decorator for Ringstrasse buildings, began to visit the Siebener Club.

In November 1896, the arch-conservative Eugeen Felix was re-elected as president of the Kunstlerhaus and the members of the organization, many of whom had been excluded from exhibitions in the past, took the opportunity to voice their opposition. Led by Klimt, they decided to form a new society based on the models of the Berlin and Munich Secession founded by Franz von Stuck in 1892. Klimt was by then the most recognized of the breakaway artists, having risen to fame as a decorator during the great building boom of the Ringstrasse. His panel paintings on the Burgtheatre theatre in 1887 won him the Emperor’s prize in 1890 making him the favourite child of bourgeois Ringstrasse culture. It was only natural then that it would be Klimt, an artist at the peak of his fame, who should assume the leadership of the new movement.

On April 3, 1897, a letter was put forth to the Kunstlerhaus announcing the formation of a new group with Klimt as president and Rudolf von Alt as honorary president. Of a total of 40 members on the list, 23 were members of the Kuntslerhaus, including Klimt, Joseph Olbrich and Koloman Moser. The group had in fact intended to stay in the Kunstlerhaus, but on May 22nd the board of directors put forth a motion of censure against the new group during their assembly forcing Klimt and the group to leave the meeting in silence. Two days later, an official letter of resignation was sent to the Kunstlerhaus announcing the resignation of twelve member artists including Stor, Olbrich, Moser, Carl Moll, and Felician von Myrbach. More resignations followed over the course of the next two years, including Hoffmann, Kurzweil and ending with Otto Wagner on October 11, 1899.

Back row from left to right: Anton Nowak, Gustav Klimt (seated), Adolf Bohm, Wilhelm List, Maximilian Kurzweil )with cap), Leopold Stolba, Rudolf Bacher. FRONT ROW, LEFT TO RIGHT: Koloman Moser (seated), Maximilan Lenz, Ernst Stohr, Emil Orlik, Carl Moll.

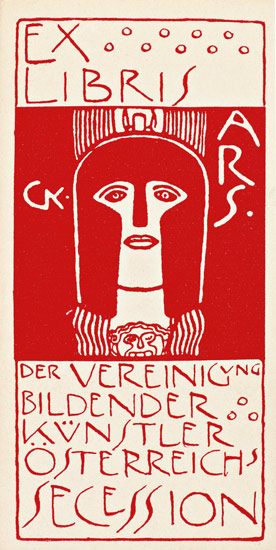

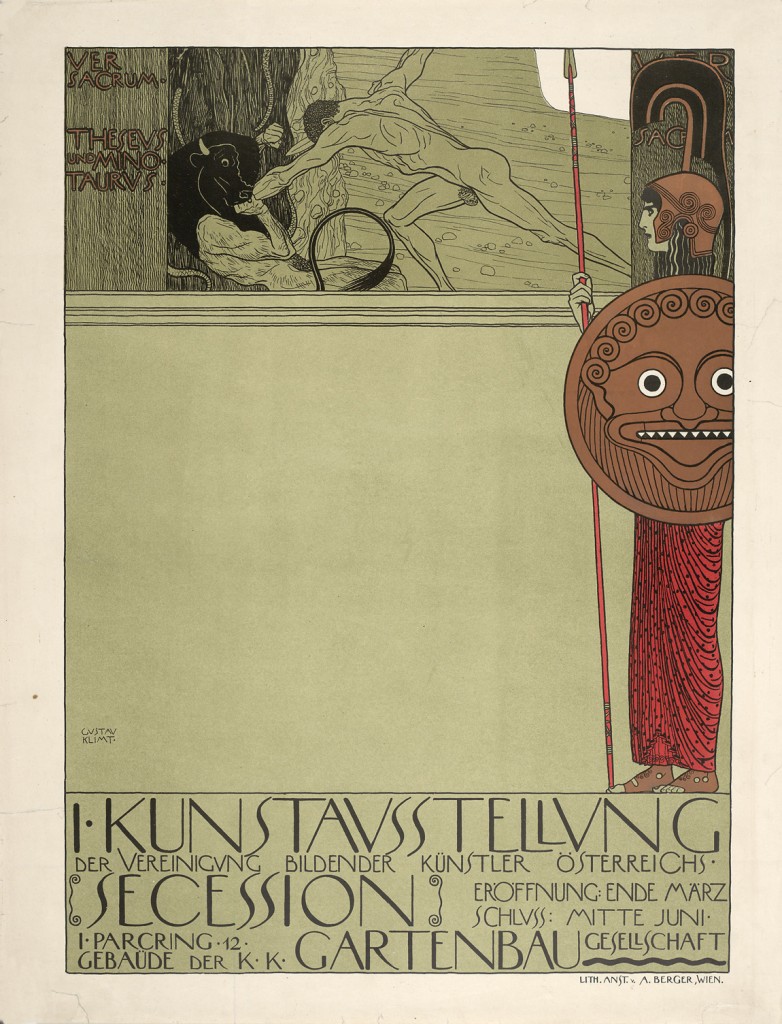

Art historians have somewhat neglected the topic of the Vienna Secession because of its apparent lack of a specific program yet it was precisely its pluralist approach to the arts which made the group unique. From the onset, the Vienna Secession brought together Naturalists, Modernists, and Impressionists and cross-pollinated among all disciplines forming a total work of art; a Gesamkunstwerk. In this respect, the Secession drew inspiration from William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts movement which sought to re-unite fine and applied arts. Like Morris, the Secessionists spurned 19th-century manufacturing techniques and favoured quality handmade objects, believing that a return to handwork could rescue society from the moral decay caused by industrialization. In spite of their critique of industrialization, they did not completely reject the classicism which had stifled its artists in the previous decades. Klimt turned to classic symbols a metaphor for the struggle against historicism and repression of the instinctual nature of man. In the first Secession poster, he uses the myth of Theseus and his slaying of the minotaur in order to liberate the youth of Athens, though here Athena is not a protector of the polis as Klimt had depicted her nine years earlier in his panel paintings of the Kunsthistoriches museum. Now Klimt presents her as the liberator of the arts, overseeing the conquest of historicism and inherited culture by the new generation of artists. In another drawing for Ver Sacrum titled ‘Nuda Veritas’, Athena holds an empty mirror to modern man, signifying a call for introspection. In both cases, Klimt subversibly distorts the myth of Athena using it as a bridge between the past and the present.

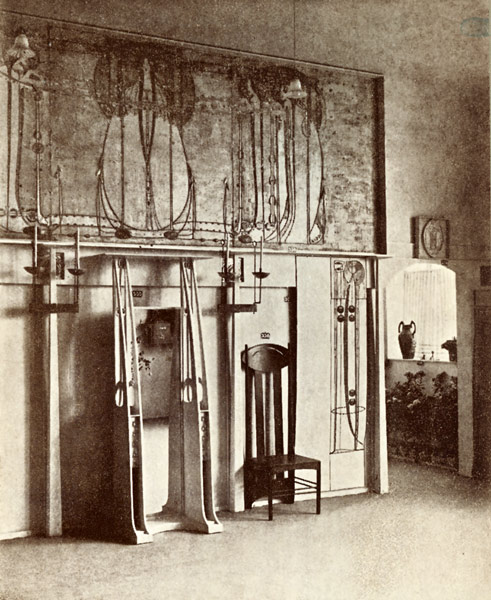

Stylistically, the Secession has mistakenly been seen as synonymous with the Jugendstil movement, the German version of art nouveau. It is true that the Secessionists incorporated many of Jugendstil elements in its work such as the curvilinear lines that decorate the facade of the Secession building. Many of the organization’s members had been working in the Jugendstil style prior to joining and the group did honour the Art Nouveau movement in France by devoting an entire issue of Ver Sacrum in 1898 to the work Alphonse Mucha. Nevertheless, the Secession developed its own unique ‘Secession-stil’ centred around symmetry and repetition rather than natural forms. The dominant form was the square and the recurring motifs were the grid and checkerboard. The influence came not so much from French and Belgian Art Nouveau, but again from the Arts and Crafts movement. In particular the work of William Asbhee and Charles Renee Mackintosh both of whom incorporated geometric design and floral-inspired decorative motifs, played a large part in forming the Secession-style. The Secessionist admiration of Mackintosh’s work was evident by the fact that he was brought to Vienna for the 8th Secession Exhibition.

Mackintosh exhibition room at the 8th Secession exhibition. Photograph of Secession Exhibition, Vienna, 1900 © Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery

The influence of Japanese design cannot be understated in relation to the Secession. Japonism had swept through Europe at the end of the eighteenth century and French artists like Cezanne and Van Gogh; both of whom were avid collectors of woodblock prints were quick to incorporate elements in their work. When Japonism arrived in Austria, the Viennese were also not immune to its influence. The Vienna International Exposition of 1873 featured a Japanese display complete with a Shinto shrine and Japanese garden and hundreds of art objects. Japanese design was quickly incorporated by the Secessionists for its restrained use of decoration, its preference for natural materials over artifice, the preference for handwork over machine-made, and its balance of negative and positive space. In a way, the Secessionists saw in Japanese design their ideals of a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’, whereby design was seamlessly incorporated into everyday life. So strong were these ties that they devoted the Secession exhibit of 1903 to Japanese art.

Klimt, in particular, began to incorporate textile patterns into his work culminating from both his exposure to Japanese textiles and the Byzantine Mosaics he studied in Ravenna, Italy in 1903. His model and long-time friend Emile Floge was a known collector of Japanese textile designs from which she drew inspiration for her own fashion line. Perhaps the most important influence especially in the field of graphic design and painting came from Japanese woodblock prints. The emphasis on flat visual planes, strong colours, patterned surfaces, and linear outlines appealed to the secessionists and helped form a bridge between fine and graphic arts. Klimt and much later Egon Schiele began to incorporate the use of flat negative space as can be seen in Klimt’s Hope II from 1908 and Portrait of Gerti Schiele from 1909.

- Japanese postcard circa early 1900’s (left) and a cover design by Hans Christiansen for Deutsch Kunst un Dekoration, 1900. (right)

- Portrait of Gerti Schiele- by Egon Schiele. Oil on Canvas. 1909

- ‘Hope II’ by Gustav Klimt. Oil, gold, and platinum on canvas, 1907-1908

SECESSION HOUSE

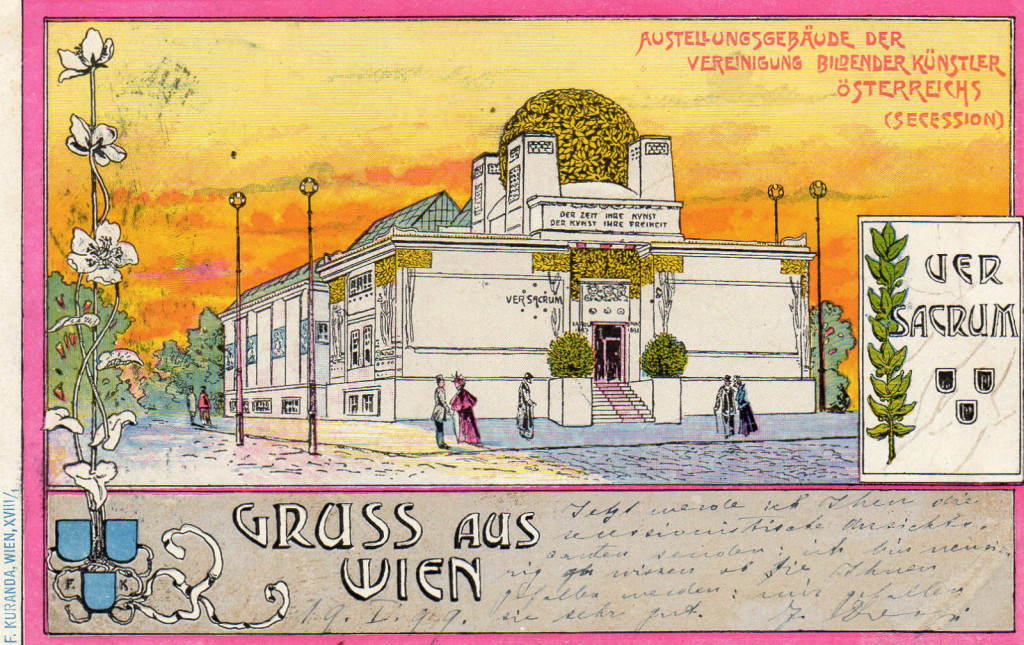

From the onset, one of the most important aims of the secessionists was to have their own exhibition building. They had been required to rent for a considerable sum the building of the Horticultural Society for the first secession exhibition in March of 1898 and had seen the need to revise exhibition spaces from the traditional Salon model. Thanks to the financial success of this exhibition which drew some 57,000 visitors; including Emperor Franz Josef himself, they were able to undertake the construction of a permanent exhibition building. The location for this building; an area of roughly 1000 square meters on the corner of Karlsplatz just beneath the window of the Academy of Fine Arts and a short walk from the Ringstrasse, was both symbolic and controversial.

The architect chosen for the project was Josef Olbrich, a young pupil of Otto Wagner and one of only three architects (Josef Hoffmann, and Mayreder) who had joined the Secession. He had worked as a chief draughtsman for Wagner on the Stadtbahn during which time he was able to absorb Wagner’s trademark art nouveau ornamental details. By the time Olbrich was designing the Secession building however, we see a drastic simplification of these Art Nouveau elements. Viewing Olbrich’s original sketches for the building, we can see a gradual reduction of decorative elements to basic geometric forms signifying a break from Wagner’s grandiose art nouveau style. Gone are the 4 pillars on the front and two more that flank the doorway. The decorative frieze we glimpse in the original sketch is also omitted, leaving a white windowless facade that foreshadows Bauhaus. (Olbrich did include a frieze by Koloman Moser on the side of the building which has since disappeared) In the 14 months of its construction, it would attract more curiosity and ridicule than any other building constructed in Vienna. Originally nicknamed ‘Mahdi’s Tomb’ or the ‘Assyrian convenience, it was not until the gold cuppola was in place that the most famous of nicknames was coined; ‘The golden cabbage.’ Like Klimt, Olbrich incorporated references to classical antiquity in the owl and gorgon (Medussa heads) decorative motifs. Signifying the attributes of Athena; the goddess of wisdom and victory, Olbrich makes her both a liberator and guardian of the arts.

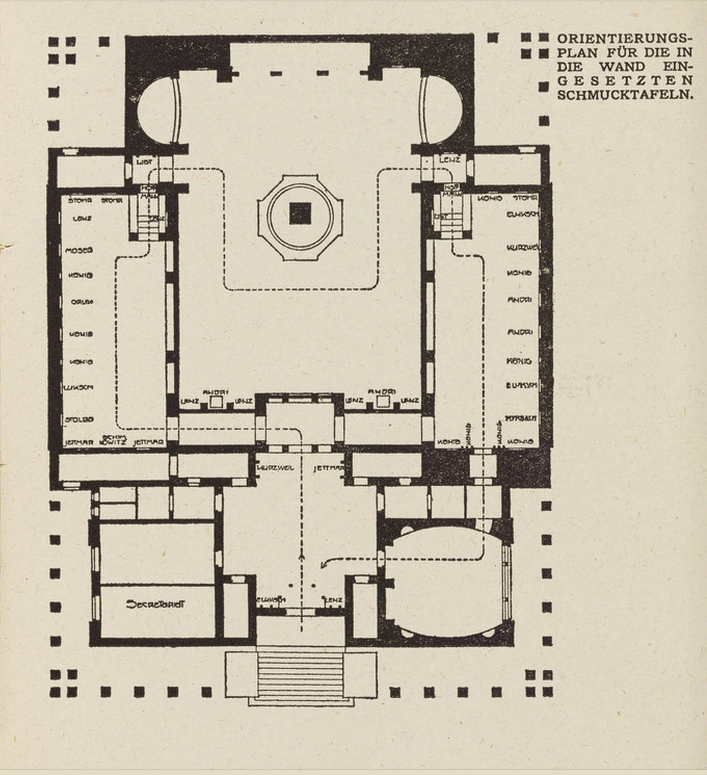

Olbrich’s building can also be seen as a precursor to functionalism in architecture. Having been responsible for the arrangement and hanging of the first Secession exhibition in the Horticultural Society building, Olbrich saw the need for a versatile exhibition place that could accommodate the group’s vision of ‘Gesamkunstwerk; that is, where all disciplines of the arts could be exhibited simultaneously. Olbrich incorporated moveable interior partitions and columns which meant that each exhibition could have its own unique layout. This created enough wall space for paintings to be hung at eye level and ample floor space so that sculpture and painting could be paired in the same exhibition.

THE SPLIT

While the presidents of the association changed in the early years, there were growing disagreements between the members of the Secession concerning the objectives of the association. On the one side was the ‘Klimt group’ who set out to include the applied arts into the Secessionist program by including designers and architects in their exhibitions. On the other side were the ‘pure painter’ members with Engelhardt at their head who felt the applied arts did not possess the same artistic quality as easel painting.

The breaking point, however, was an incident involving Carl Moll and the Galerie Miethke- a prominent gallery in Vienna. In the spring of 1905, the gallery sought the curatorial advice of Moll who wanted to run the gallery as a commercial outlet for the artists of the Secession. This proposal was of course seen as a conflict of interest by the Klimt group who regarded the move as the commercialization of their association. In the end, the decision to become involved with the gallery was put to a vote and the Klimt group lost by one vote. As a result, the Klimt group resigned from the Secession leaving behind the most valuable asset: the building. The association saw a reduction in the number of official members from 64 listed in the 23rd exhibition catalogue (May 1905) to 48 members listed in the 24 exhibition catalogue (November- December 1905).

While the Secession would continue at least in name for another 13 years, the quality of the exhibitions never matched the creative vision of Klimt, Olbrich, Hoffmann and Moser during the first 8 years.

R. Rosenman, © 2017

Vergo, Peter. Art in Vienna. London: Phaidon Press Limited. 1975

Varnedore, Kirk. Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture and Design. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. 1986

West, Shearer. Fin de Siecle: Art and Society in an Age of Uncertainty. New York: The Overlook Press. 1994

Schorske, Carl E. Vienna: Politics and Culture. New York: Vintage Books. 1980