The Wiener Werkstätte was founded in 1903 by Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, both of whom had been key members of the Vienna secession. The primary goal of the company was to bring good design and craft into all areas of life within the fields of ceramics, fashion, silver, furniture, and the graphic arts. It was in keeping with the Vienna Secession’s idea of the Gesamkustwerk– a total work of art. Just as the Vienna Secession had reacted against the old neo-classical style of the ‘Association of Austrian Artists’, the Wiener Werksätte had initially been promoted as a declaration of modernity over the old order. A small pamphlet from 1905 outlined their program: “The limitless harm done in the arts and crafts field by low-quality mass production on the one hand and by the unthinking imitation of old styles on the other is affecting the whole world like some gigantic flood…It would be madness to swim against this tide. Nevertheless we have founded our workshop. Where appropriate we shall try to be decorative without compulsion and not at any price” From the onset, the Wiener Werkstätte encouraged its patrons to look beyond the material value of objects and to embrace geometric symmetry over surface ornament. We need only to look at Moser’s logo design and the flower motif based on the golden section to see how much these architectural principles dictated the company’s early designs.

Graphic Arts

The Wiener Werkstätte devoted an entire floor of it’s factory at 32-34 Neustiftgasse to graphic art. Here it produced stationery, ex-libris, book design and what some consider its crowning achievement: postcards. In total 925 postcards were printed between 1907-1920, some in very limited runs and others in runs of up to 1000. Encompassing primitivism, expressionism and art deco, these cards reflect the vibrant art scene of pre-war Vienna. Although the WW officially began producing postcards in 1907, it did issue a Christmas card and New Year’s card based on designs by Carl Otto Czeschka in 1905. Only about 100 of these cards were printed and they remain extremely rare.

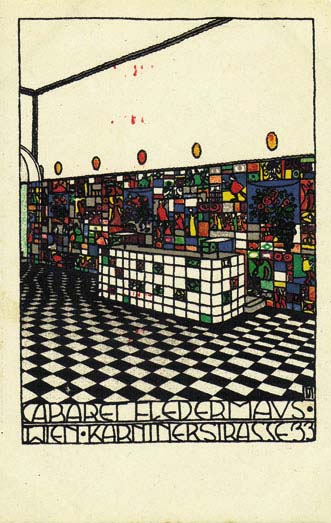

Postcards as a commodity were an Austrian invention with the first postcards appearing around 1869 though it wasn’t until chromolithography techniques began to be used in the late 1890s that postcard collecting became fashionable. It is thanks to this trend in collecting that many of the Wiener Werkstätte postcards we find today are unused and in surprisingly good condition (the only exception being the greeting cards which were printed in small runs and often mailed). The idea of using postcards to publicize new events and ideas had already been employed by Koloman Moser, Josef Olbrich and Josef Hoffmann for the Vienna Secession so when the Wiener Werkstätte needed to expand their client base, they turned to postcards to promote their projects such as Kunstschau in 1908 (WW 1-4) and the Cabaret Fledermaus in 1907. (WW 74,75). They also issued postcards with views of Berlin and Karlsbad in order to promote the new branches there and a series to mark the Procession in Honour of the Emperor’s Jubilee in 1908 (WW 164-186). The Wiener Werkstätte also produced approximately 200 fashion postcards to promote its fashion department opened in October 1910.

The first year of postcard production also coincided with a stylistic shift in the company’s design. This was mostly a result of the departure of Koloman Moser who had become increasingly dissatisfied with the administration. With his departure, the aesthetic unity of the WW designs, which had primarily been executed by Moser and Josef Hoffmann, gave way to a new broader style based on Mycenaen and folk styles. The motif of the neutral square and the checkerboard gave way to the jagged woodcut marks, Byzantine whirls, and fragmented mosaic work. Most importantly, the architectural principles that had dominated the early designs of the Wiener Werkstätte began to be abandoned in favour of pictorial surface ornament. In this respect, the Wiener Werkstätte began to lose touch with Moser and Hoffmann’s vision of design that rejected material value and applied ornament.

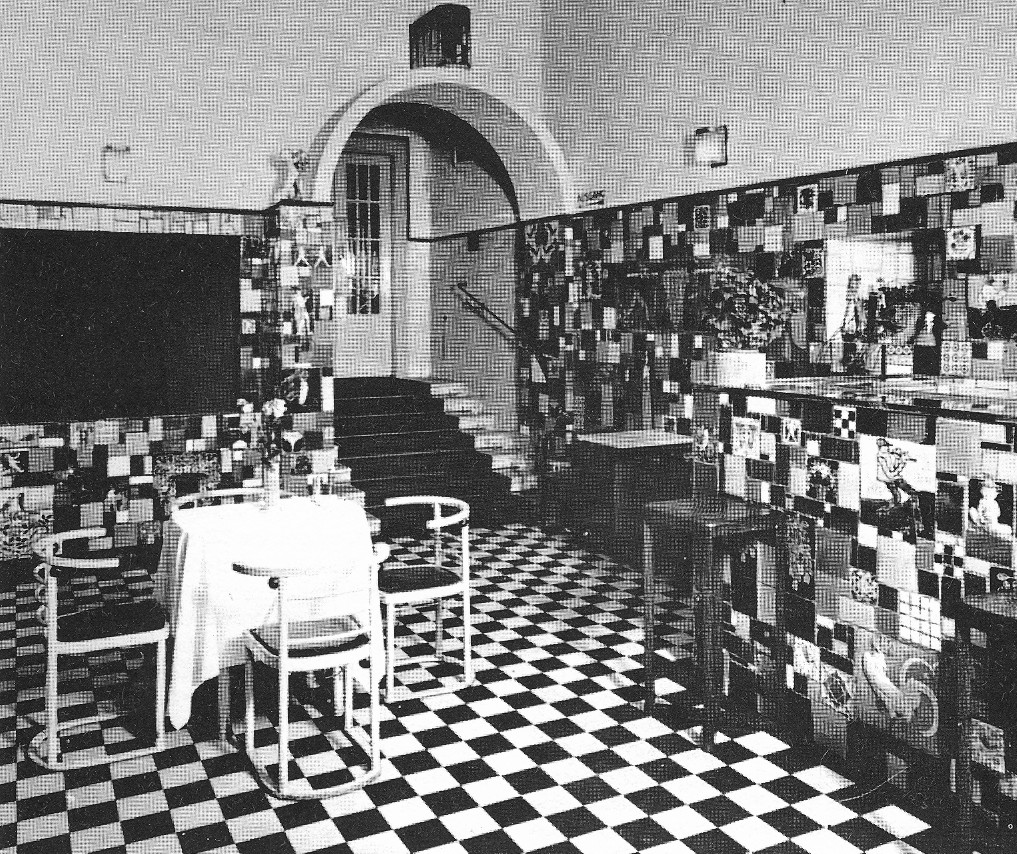

The forerunners of this new style were Carl Otto Czeschka, Bertold Löffler and Oskar Kokoschka, all of whom either taught or were students at Kunstgewebeschule in Vienna. These artists themselves had already been responsible for the stylistic shifts in the company. Bertold Löffler had been commissioned to work on the Kabaret Fledermaus in 1907 and his fragmented mosaics, which covered the walls of the theatre were an affirmation of the dominance of stylization over architectural order. It is thanks to Hoffmann’s postcard of the Kabaret café’s interior that we know the colour palette of this mosaic work.

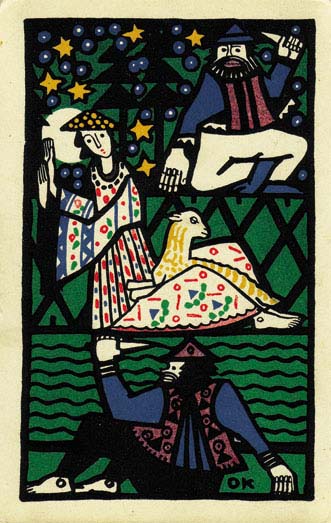

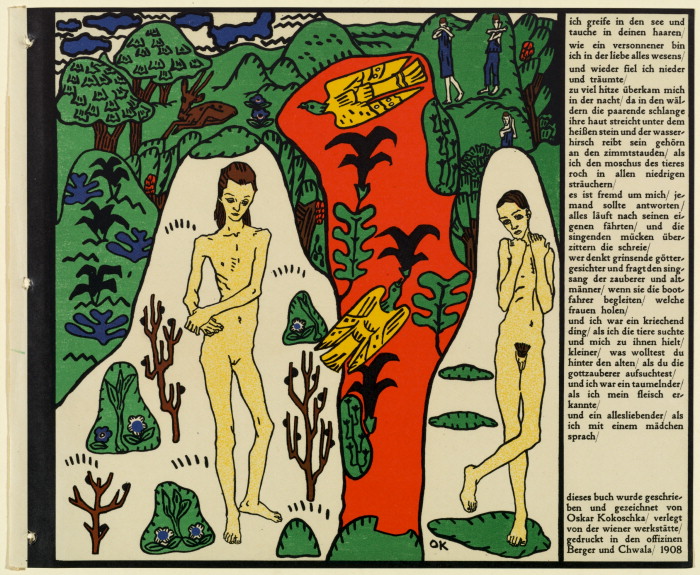

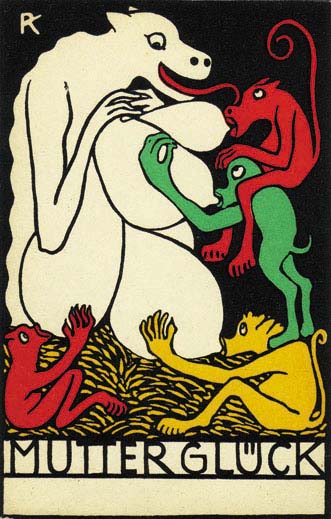

Kokoschka’s illustrated book in 1908 The Dreaming Youths, reflects the interest in figural fantasy that was beginning to permeate Viennese art. The increasing use of primary hues, broken lines, and organic forms floating in fields of space; all point to an interest in child psychology and the notion of the uncorrupted imagination. This was after all Freud’s Vienna where a prominent wealthy class could indulge in psychoanalysis. We see this interest in primitivism also figure prominently in the 1907-08 postcard designs of Rudolf Kalvach and Carl Krenek (both fellow students of Kokoschka at the Kunstgewebeschule) whose use of primary colours and woodcut-like marks are beautiful examples of pre-Expressionism.

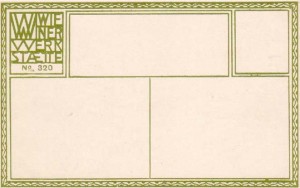

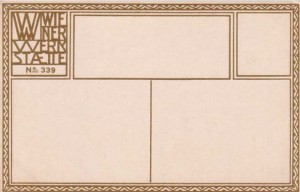

The interest in primitivism would also be coupled with an interest in folk myths and fairy tales exemplified in Carl Otto Czeschka’s 1909 children’s book Die Nibelungen, which portrayed neo-viking sagas. This interest was synonymous with a new surge in Nationalism egged on by a more powerful peasant class and the increasing influence of the staunchly anti-French and anti English Franz Ferdinand. Bertold Löffler’s edition of cards for the Volkskeller in Salzburg (WW 911-920) as well as Remigius Geyling’s edition of cards for the Emperor’s Jubilee depicting picturesque peasant costumes (WW 164-186) all reflect this interest in folk culture.

‘The Dreaming Youth’- Oskar Kokoschka

WW #99 by Rudolf Kalvach.

The numbering system

The numbering system of postcards has caused much confusion to collectors over the years. Although the postcards were printed with numbers from 1-1012, there were actually only 920 numbers assigned; 5 of which were assigned twice (#164,394,395,396,397) thus bringing the total number produced to 925. The actual numbering system is: 1-920,962,1000-1012 with the missing numbers being 614, 618, 622, 624, 681, 737, 752, 756, 805, 806, 807, 847, 907, 1006.

Of the 92 missing numbers, it is assumed that they were never published. Not all the cards between numbers 1-725 had been published by 1912. Since numbers between series were left unused, cards were inserted much later in order to complete the numbering. There is also a rare edition of postcards by Bertold Loffler for the Volkskeller Salzburg which are numbered 1-10 but are actually identical to #911-920 with the exception of the address of the Volkskeller on the verso. Click Here to download a pdf of the artist list.

From 1913 to 1919, there was a break in the company’s production of postcards. Whether the interest in postcards had by then faded or if World War 1 limited the potential for tourism and in turn the need for postcards is a mystery but there was apparently one last attempt to revive them in 1919 and 1920 which proved unsuccessful. Eventually, the economic crisis and the accompanying decline of the upper class would force the Wiener Werkstätte to close its business for good in 1932.

The Verso

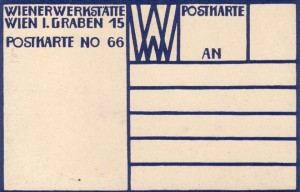

The blue verso was used in 1907 for numbers 11-104. The yellow was used in 1908 for cards 105-188. The green verso was used from 1909-1913 and then a black verso was produced briefly from 1919-1920. Numbers 1-168 were occasionally overprinted which accounts for some of these having a green or blue verso rather than a yellow one.

- Blue Verso used on postcards 11-104 produced in the first year, 1907.

- Yellow verso used on postcards 105-188 produced in 1908.

- Variation of yellow verso

- Green Verso used from 1909 to 1913.

- Brown verso used on postcards #288-290 (Egon Schiele) and # 328-333 (Ludwig Jungnickel) as well as others.

- Large format brown verso used on Mela Koehler postcards #363-372

- Russian proverb cards used on #384-395 by Elena Luksch-Makowska.

- Verso used for cafe-restaurant cards (#408-412, 486-490)

- Verso used for cafe-restaurant cards (#408-412, 486-490)

- Verso used for cafe-restaurant cards (#408-412, 486-490)

- Verso for no. 574

R. Rosenman © 2012