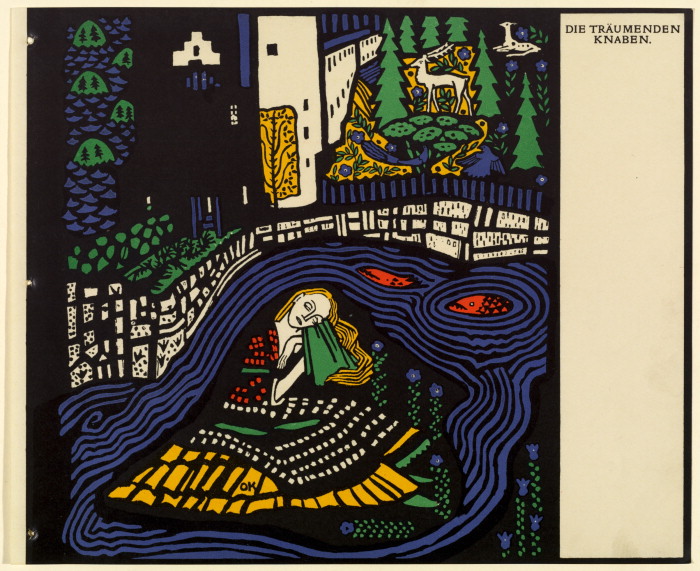

Oscar Kokoschka is credited as being the artist who broke with the Jugendstil style–Austria’s equivalent of Art Nouveau– to create Austrian Expression. The true father of Expressionism in Austria was in fact the young and timid painter Richard Gerstle, but because of his early death from suicide and the relatively small body of work he left behind, the title is often given to Kokoschka instead. Of all of Kokoschka’s works, historians regard his illustrated book Die träumenden Knaben (The Dreaming Youths) as an important work that best shows the transition from Jugendstil to Expressionism. It also reflects a young and insecure Kokoschka who, not having found his place or unique style, was borrowing from the eclectic styles that were prevalent in early 20thcentury Vienna. In addition, the book provides an insight into Kokoschka’s psychology and his pre-occupation with trying to express Eros and death through art and poetry. The Dreaming Youths is a juxtaposition of opposites, where notions of beauty and the grotesque, love and sexual violence, and reality and the subconscious are constantly blurred.

Oscar Kokoschka is credited as being the artist who broke with the Jugendstil style–Austria’s equivalent of Art Nouveau– to create Austrian Expression. The true father of Expressionism in Austria was in fact the young and timid painter Richard Gerstle, but because of his early death from suicide and the relatively small body of work he left behind, the title is often given to Kokoschka instead. Of all of Kokoschka’s works, historians regard his illustrated book Die träumenden Knaben (The Dreaming Youths) as an important work that best shows the transition from Jugendstil to Expressionism. It also reflects a young and insecure Kokoschka who, not having found his place or unique style, was borrowing from the eclectic styles that were prevalent in early 20thcentury Vienna. In addition, the book provides an insight into Kokoschka’s psychology and his pre-occupation with trying to express Eros and death through art and poetry. The Dreaming Youths is a juxtaposition of opposites, where notions of beauty and the grotesque, love and sexual violence, and reality and the subconscious are constantly blurred.

Kokoschka was a twenty-one year old student at the Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna School of Applied Arts) when he was commissioned by the company Wiener Werkstätte to create The Dreaming Youths. It’s progressive and wealthy director Fritz Warendorfer was once described by writer and actor Egon Friedell as “an intelligent gentlemen with a great deal of money and taste- two things we all know practically never come together”. Warendorfer was a strong supporter of the progressive ideas of the Vienna Secession and acquainted with some of its members like Carl Otto Czeschka, Koloman Moser and Frank Myrbach who were teaching at the Kunstgewerbeschule. The company had by then regularly employed teachers and students; particularly those enrolled in Czeschka’s classes, to create designs for the company’s postcards. Artists involved in this product included Mela Koehler, Maria Likarz-Strauss, Rudolf Kalvach and of course, Kokoschka who in addition to postcard designs, produced flower paintings, narrative cameos and landscape scenes.

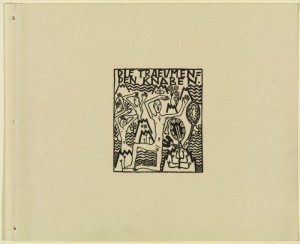

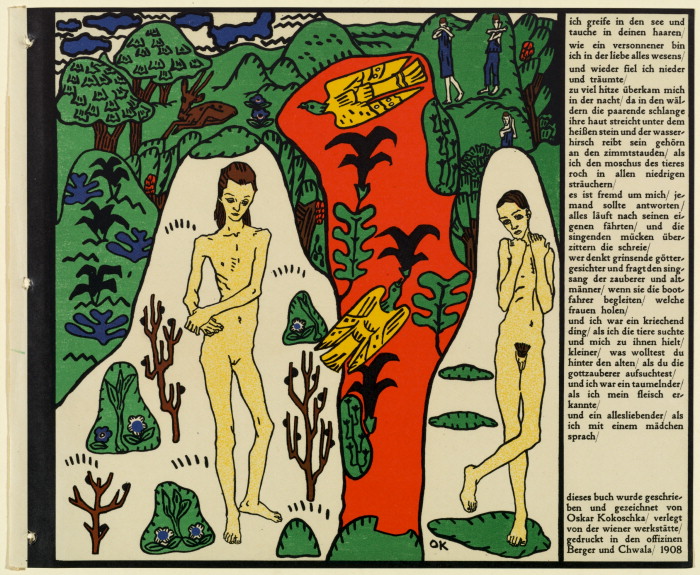

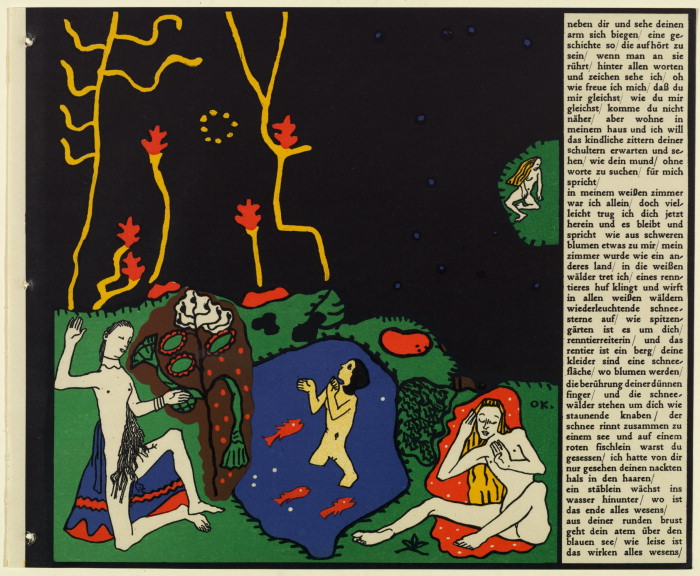

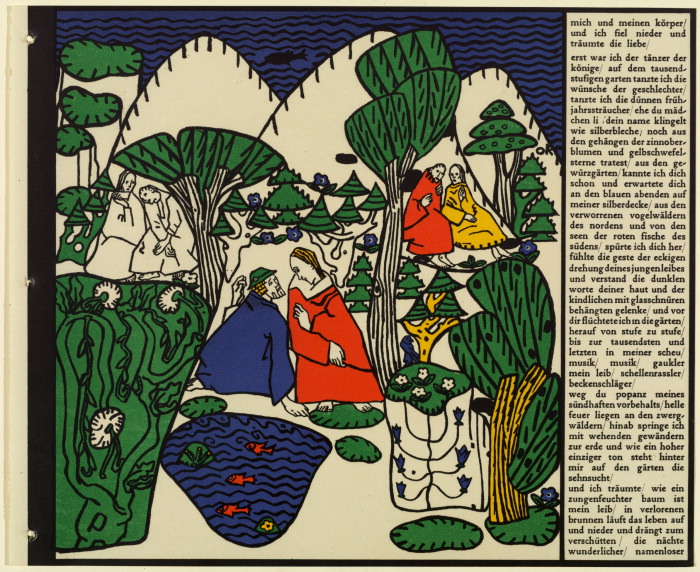

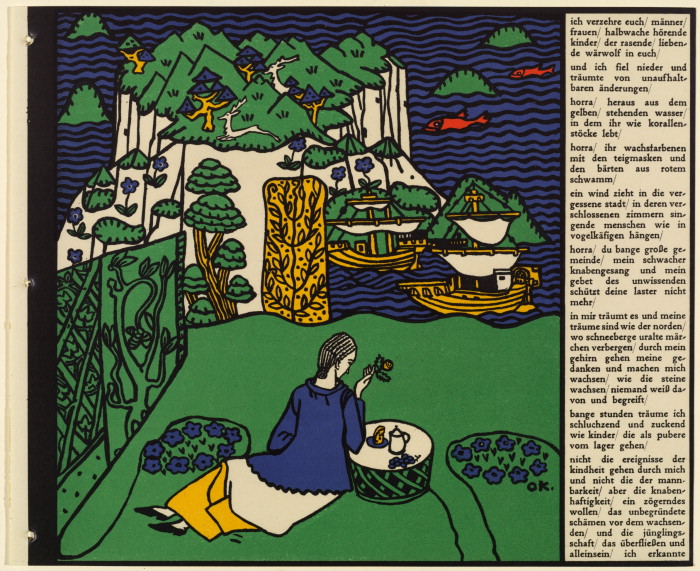

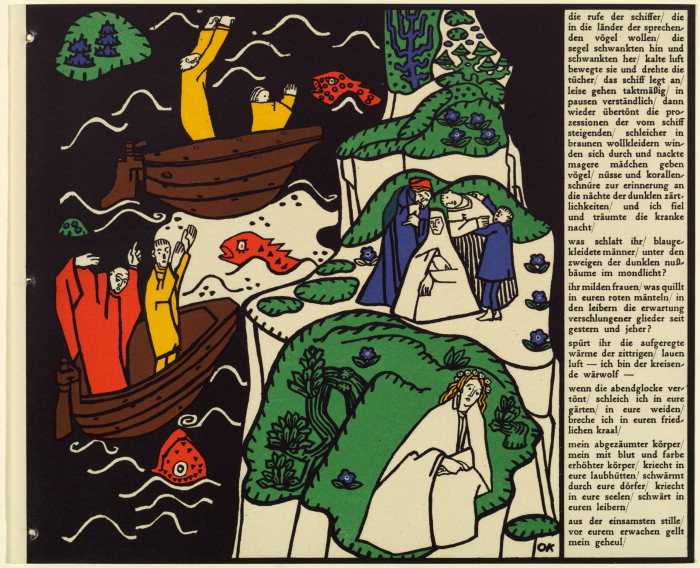

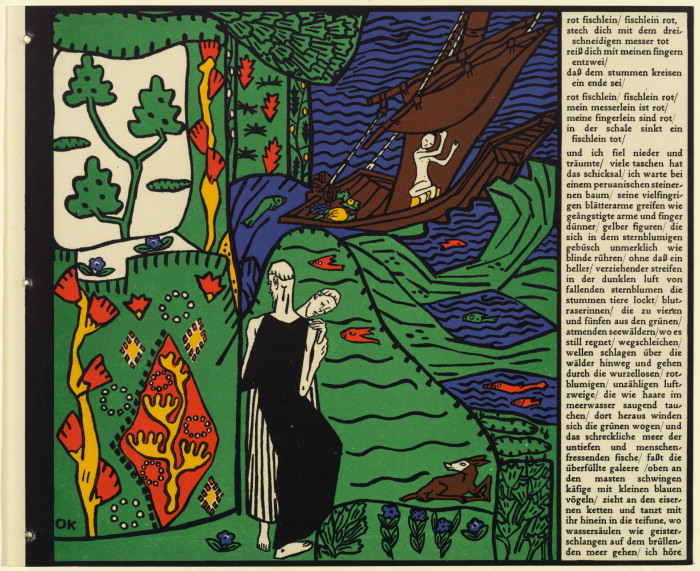

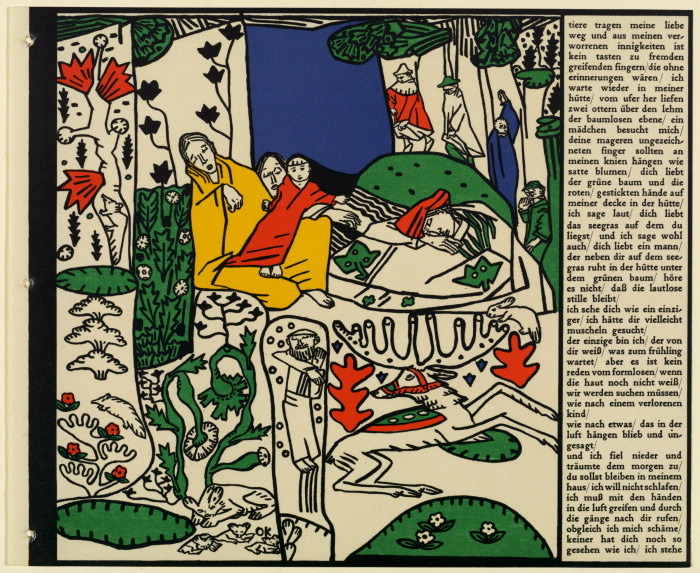

The Garden of Dreaming Youths was Kokoschka’s first large commission by the Wiener Werkstätte at the recommendation of Czeschka in late 1907. Initially the commission was to create a children’s picture book printed but Kokoschka claimed to have followed the brief only as far as the first page. In the subsequent pages, there follows a stream-of conscious narrative style prose chronicling the story of a young boy and a heroine named Li in a fantastical lost bird-forest of the north. The poem combines symbolist poetry-style of the late 19th century with traditional verse forms of German folk-poems. As the story progresses, the text of the book becomes both inaccessible and inappropriate for children not only on account of its style, but also because of its references to rape and self-mutilation. The prose-poem was accompanied by eight colour lithographs that, with the exception of the first four, don’t seem to correspond to the text.

From what we know about this period of his life, Kokoschka seems to reflect on his own state of mind at the time, placing himself as the character of the boy. The girl in the story was in fact a Swedish girl named Lillith Lang, a few years his junior at the Kunstgewerbeschule and whom Kokoschka was romantically involved with. In his autobiography, Kokoschka describes her as often wearing a red-peasant-weave skirt; “Red was my favorite color and the book was my first love letter. But she had already gone out of my life by the time it appeared.” [1]

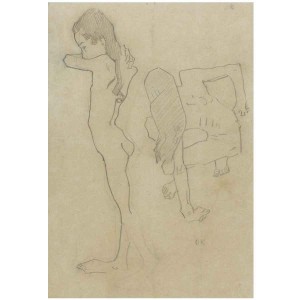

A series of nude studies of Lang by Kokoschka made during this period, show strong similarities to the illustrations in the book. One particular study showing Lang standing with her hands on her hips is perhaps the clearest indication that she is the heroine of the story for the same pose appears in the final and best known lithograph The Girl and I in the book. Incidentally, it is the only lithograph where the two figures are not subordinate to the background elements implying there exists a union between the two figures.

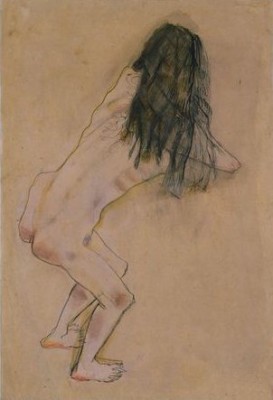

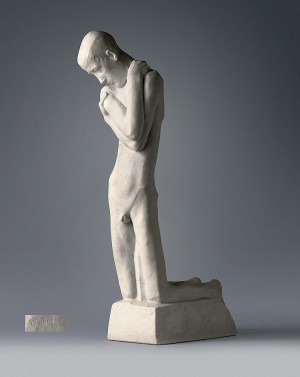

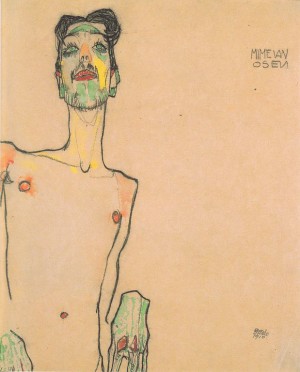

Lang’s boyish pre-pubescent figure must have appealed to Kokoschka as it allowed him to emphasize the angular contours of his model. Stylistically these studies, with their emphasis on unbroken contour lines, show the strong influence of Jugendstil, yet we also glimpse the beginnings of expressionism in the exaggeration of gesture and the angular quality of the line. We can see a direct reference to the Fountain of Youth by sculptor George Minne whose balance between restrained modeling and expressive elements within his sculptures had a profound influence on Austrian artists. These exaggerated gaunt figures appear in Klimt’s Beethoven Freize and are brought to a climax in Schiele’s drawings of the mime artist Mime van Osen. In Minne’s work, Kokoschka saw the breaking away from the flat two-dimensional quality of Jugendstil and it’s emphasis on surface decoration. Referring to Minne’s sculptures at the second Kunstschau exhibit in 1909, Kokoschka writes:

“In their chaste forms and their inwardness, I seemed to find a rejection of the two-dimensionality of Jugendstil. Something was stirring beneath the surface of these figures of youths, something akin to the tension which, in Gothic art, dominates space and indeed creates it.” [2]

- George Minne- Kneeling Youth, 1898.

- Egon Schiele- Portrait of mime Van Osen, 1910.

Another major influence on Kokoschka during this period his teacher Carl Otto Czeschka. Kokoschka was in his third year and currently enrolled in Czeschka’s Technical School for Painting class when the Wiener Werkstätte commissioned him for the book. Contrary to its title, the class focused primarily on graphic art and it’s unsurprising, given Kokoschka’s limited education in easel painting, that he found his place in the class. The emphasis on two-dimensional design, the lack of Jugendstil decorative influence, the preference for gouache over oil paint, and the use of solid ungradiated colour, all appealed to him and he quickly adopted Czeschka’s illustration technique. When we compare The Dreaming Youths and Czeschka’s children book Die Niebelungen, published a year earlier by Gerlach and Schenk, we see that Kokoschka adopted Czeschka’s method of using a cream coloured paper which was then covered, with the exception of the figures, by watercolour and gouache.

Another major influence on Kokoschka during this period his teacher Carl Otto Czeschka. Kokoschka was in his third year and currently enrolled in Czeschka’s Technical School for Painting class when the Wiener Werkstätte commissioned him for the book. Contrary to its title, the class focused primarily on graphic art and it’s unsurprising, given Kokoschka’s limited education in easel painting, that he found his place in the class. The emphasis on two-dimensional design, the lack of Jugendstil decorative influence, the preference for gouache over oil paint, and the use of solid ungradiated colour, all appealed to him and he quickly adopted Czeschka’s illustration technique. When we compare The Dreaming Youths and Czeschka’s children book Die Niebelungen, published a year earlier by Gerlach and Schenk, we see that Kokoschka adopted Czeschka’s method of using a cream coloured paper which was then covered, with the exception of the figures, by watercolour and gouache.

Throughout his life, Kokoschka seemed to present an image of himself as the original outsider artist- an ‘enfant terrible’ who forged new styles rather than emulate existing ones- a narrative which was also spread by Adolf Loos, his great benefactor and supporter. Kokoschka claims that he rarely attended the Secession exhibitions or the old masters exhibitions at the Kunsthistoriches Museum and Museum Theresia Platz, preferring instead the ethnography department at the Naturhistoriches Museum.

We now know that while Kokoschka might have felt alienated from the work of his contemporaries and the old masters, he strove to emulate them. This is most evident when we compare the style of The Dreaming Youths to the work of Kokoschka’s classmate, Rudolf Kalvach. Kalvach is the unsung hero of Expressionism- an exceptionally talented Croatian-born artist whose career was cut short by the onset of poverty and schizophrenia. It is in Kalvach’s work that we first see a drastic departure from the decorative elements of Jugendstil through a simplification of colour and form. His use of flat plains of colour, angular contours, and blocked fields of space must have caught Kokoschka’s attention and he quickly began to imitate Kalvach’s style, as Czeschka recalled in 1951:

“In October, I assigned Kokoschka to a large table next to the window. His neighbour was Kalvach the Croatian, son of a likeable, honest locomotive engineer. Kalvach’s work had a very special quality, he was quite talented and poor, too. Pretty soon, Kokoschka started making things like Kalvach–God! Slowly, I had to show this little Mimosa Kokoschka the he was heading entirely in the wrong direction– that you can’t do things like that– you have to find your inner self. Because he had seen very little art, I told him he had to look at a lot and try to understand the problems, graphic elements, translation, the shorthand simplification of the subject– all this was Greek to him. Very slowly he found himself. Without his noticing, I was able to bring him to create works that he’s still exhibiting in his shows today.” [3]

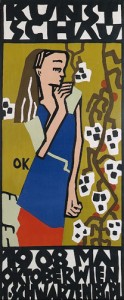

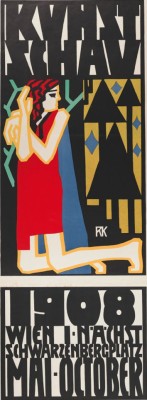

Even today, it is difficult to distinguish the work of Kalvach and Kokoschka from this period as is evident from their poster designs for the Kunstschau exhibit in 1908.

- Kokoschka- Poster for The Kunstschau. 1908.

- Rudolf Kalvach- Poster for the Kunstschau, 1908. Image from the collection of Leopold Museum, Vienna.

Kokoschka’s new ‘borrowed’ style could not have come at a better time in Austrian society. The birth of psychoanalysis, which gained popularity among intellectual circles in Vienna, contributed to an interest in child psychology, and in particular to the idea of children’s uncorrupted imagination. As a result, there was a new appreciation for the naïve styles like folk art as they reflected the larger phenomenon of Primitivism that was beginning to permeate the arts. Seizing on this new aesthetic, Kalvach, and in turn Kokoschka, sought to simplify elements in their work. In The Dreaming youths, Kokoschka uses vivid primary colours and reduces perspective to simple blocked and geometric spatial zones. Gone too are the sinuous lines of Jugendstil, replaced with an angular and heavy lines that resemble woodblock engravings.

Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, first published in 1900, also likely had a strong impact on Kokoschka and his fascination with dreams and the subconscious. He uses the garden and animals as a symbol for the subconscious, as well as a reference to the creation myth. While it is an ideal setting for a story about adolescent sexual awakening, it is also an awakening of the mind. Again Kokoschka might have been borrowing here from Kalvach whose painting ‘Indian Fairy tale’ (1907) also showed characters inhabiting a sinister garden.

The narrator inserts both himself and Li into the iconography of the garden. Animals like reindeer, blue birds, and red fish continually appear in pairs, yet the narrator and Li rarely appear together in the same frame implying that their encounters only occur in the narrator’s dreams. In one instance, he transposes the colour red of Lillith’s dress onto fish, which he then proceeds to mutilate:

“Red fishling/ fishling red

with a triple-bladed

knife I stab you dead

with my fingers rend you in two/

that there will be an end

to this soundless circling.

Red fishling/ fishling red/

My little knife is red/

In the dish there falls a

Fishling dead”

In another instance, he refers himself as a warewolf that appears in Li’s dreams,

“I am the circling warewolf–….before you awake my howls echo all around

I consume you/ men/ woman/ half awake listening children.

The frenzied loving warewolf in you.”

Kokoschka’s narrator seems to continuously move between emotional states of love and violent fantasies like these which eventually become indistinguishable from each other. As his dreams become progressively more violent, his desire for Li turns to dread. In this sense, Kokoschka’s narrator is the embodiment of the conflict between the Eros and Death, which Freud had first proposed in The Interpretation of Dreams and expanded in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). In Freud’s interpretation of child sexuality, Thanatos (the death drive) merges with Eros during the move from childhood to adult sexuality .The sex drive, in direct conflict with the death drive, turns the sex act into a rape fantasy. As he makes clear near the beginning of the story, the narrator is aware of being between these two states and the anguish and shame that it brings him:

“Not the events of

Childhood move through me

And not those of manliness/ nut boyishness/ a hesitant desire/ the unfounded feeling of shame before what is growing/ and the stripling state/ the over-Flowing and solitude/ I perceived myself and my body/ and I fell down and dreamt love.”

Given the violent and ambiguous content of the book, it is not surprising that the Wiener Werkstätte struggled to find a printer for the book when Kokoschka delivered the drawings on February 4th, 1908. In spite of Kokoschka’s drastic change of direction from the original commission, Warendorfer recognized the uniqueness of the book and championed to have it printed, as we learn in a letter to Czeschka:

“Right now we’re printing a story book by Kokoschka. First we tried to have it printed by Reissler at his cost because we heard that he was interested in working with us and was willing to take the risk for doing the work. But when he saw Kokoschka’s material, the beast came out and he wrote us that, in light of the emerging trend, it would be hopeless to try to sell this kind of book– what a swine, he wanted us to give him some corny fife and dream. But now the Kokoschka stuff is so interesting that even though God know we don’t have any money, we’re going to print it after all, 500 copies. Maybe we’ll sell them at the show.” [4]

The show Warendorfer was referring to was the Kunstschau in the summer of 1908- an international art exhibition organized by the Wiener Werkstatte, the Kunstgewerbeschule, and the Klimt group which had left the Secession 3 years earlier over a dispute with the rest of the members. Kokoschka was invited to participate at the recommendation of Czeschka and, at his insistence, a small room was allocated solely for him. The Dreaming Youths, or at least some of its pages did indeed make it into the show, as the catalogue lists a ‘storybook’ by Kokoschka under the catalogue numbers 16, 17, 26, and 27. He also painted a large tapestry cartoon called the Bearer of Dreams (now sadly lost) and a painted clay bust self-portrait with mouth ajar titled The Warrior.

According to Kokoschka, his exhibition room provoked horror in the Viennese public who left ‘bits of chocolate and other debris’ in the mouth of the bust. The room soon became nicknamed ‘the chamber of horrors’ while Kokoschka was dubbed the Oberwildling –chief savage– by the critic Ludwig Hevesi.[5] Unsurprising, The Dreaming Youths was not a commercial success and only a few copies of the initial 500 printed were sold at the show and afterwards. The remaining 275 of them were purchased by Kurt Wolff Verlag in Leipzig who republished them in 1917, once again to a mild reception. Neverthless, the scandal of the initial exhibition of the book at the Kunstschau, had a positive outcome for Kokoschka. It led to his participation in the second Kunstschau exhibit a year later where he caused even more scandal with his expressionist play ‘Murderer, Hope of Woman. In the wake of the scandal, Kokoschka came under the patronage of the architect Adolf Loos who encouraged him to concentrate on portraiture and arranged a series of commissions from Vienna elite.

Kokoschka- Poster design for ‘Murder, Hope of Woman’, Kunstschau 1909.

Osckar Kokoschka- ‘Self Portrait as Warrior’, 1909. Image from The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

By then, Kokoschka had drastically altered his style. The Jugendstil contour-line was soon replaced by broken hatched lines, and the solid vivid colours gave way to low-chroma blended colour. He had made the leap from Jugendstil to Expression and until his death in 1980, would never return to the brief and daring style of Dreaming Youths again.

Roberto Rosenman, 2016.

Notes

[1] Kokoschka, Oscar, My Life (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974) 20

[2] Kokoschka, Oscar, My Life (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974) 22

[3] Guggenheim Museum, Oscar Kokoscka, Works on Paper: The Early Years (New York, Guggenheim Foundation, 1994) 21

[4] ibid, 19

[5] Kokoschka, Oscar, My Life (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974) 21

Bibliography

Allen, Thomas B. Vanishing Wildlife of North America. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1974.

Cernuschi, Claude. Re-casting Kokoschka : ethics and aesthetics, epistemology and politics in Fin-de-Siècle Vienna. Madison [u.a.] : Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press [u.a.], 2002.

Kokoschka, Oscar. My Life. London: Thames and Hudson, 1974.

Guggenheim Museum. Oscar Kokoscka, Works on Paper: The Early Years. New York, Guggenheim Foundation, 1994.

Vergo, Peter. Art in Vienna, 1898-1918: Klimt, Kokoschka, Schiele and Their Contemporaries. London: Phaidon, 1975.

[hr]